Google CTF 2021: Weather

Weather

I heard it’s raining flags somewhere, but forgot where… Thankfully there’s this weather database I can use.

- Challenge file: weather

This was a really fun x64 Linux ELF reversing challenge that ended up scoring 189 points with 56 solves. I learned how printf can be extended at runtime, different disassembly techniques, and the power of dynamic tracing! Overall, I had a lot of fun with this one and I’m glad I didn’t give up on it :)

Taking a look in Ghidra

The first step I took was loading weather in ghidra and locating main.

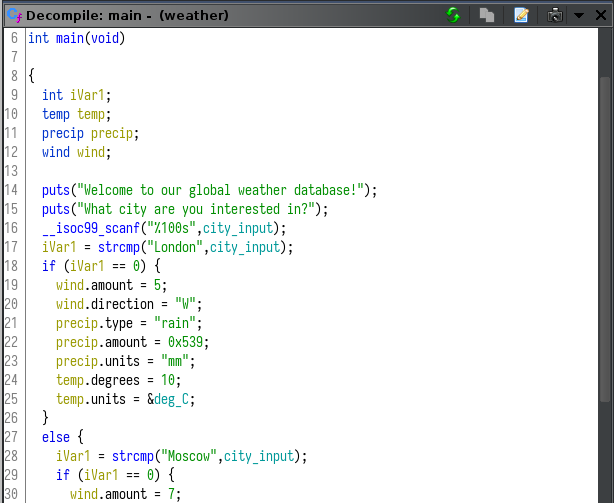

Main

Main reads user input, and initializes some structs based on string matching against a few hardcoded city names. After initializing the wind, precip, and temp structs, it displays that information using printf and some weird format specifiers I hadn’t seen before.

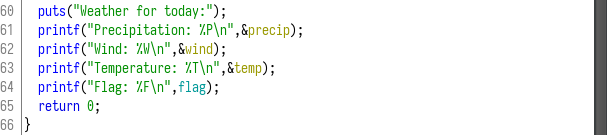

And finally, at the end there is a call to printf that looks very interesting:

printf("Flag: %F\n"), flag);

Here’s a simple interaction with the binary:

Welcome to our global weather database!

What city are you interested in?

Miami

Weather for today:

Precipitation: 100ml of sweat

Wind: 1km/h NE

Temperature: 31337°F

Flag: none

Custom printf formatting

After checking out main, I clicked through the initialization functions _INIT_0 and _INIT_1 since there must be something happening before main to make printf work this way.

There are a dozen calls to register_printf_function which is a GNU extension to the C standard library documented here. In short, the parameters to know about this function are:

register_printf_function(

// The character that triggers this handler.

// (e.g. the 'F' in %F for the flag handler)

char specifier,

// The function to call when the specifier is found.

// Note, it's not really void* but nobody has time to

// remember C's function pointer syntax, and void*

// works pretty much anywhere when you want to be lazy.

void* handler,

// Also a function pointer. This tells printf how many

// arguments are consumed when this specifier is used.

void* arginfo);

Looking at _INIT_1, I recognized W, P, T, and F from main, and according to their arginfo function, they all consume one argument. This makes sense, after all; in printf("%s %d", "hello", 4); you would expect "%s" to consume the first argument "hello", then "%d" can consume the next argument 4. Here’s how the custom formatter formats the wind struct:

struct wind {

int amount;

char* direction;

};

int Wind(FILE *fd, undefined8 param_2, wind ***wind) {

return fprintf(fd,"%dkm/h %s",(**wind)->amount,(**wind)->direction);

}

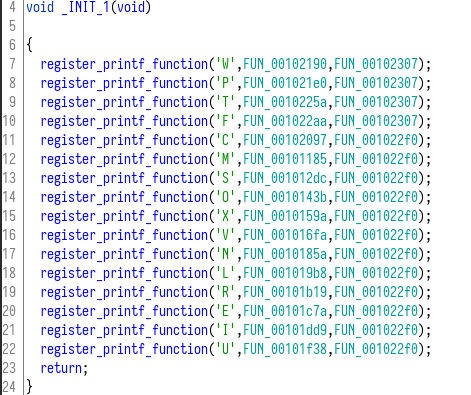

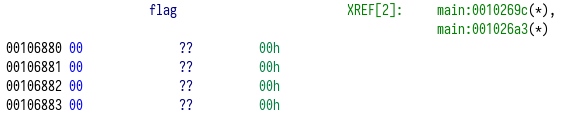

However, the remaining handlers consume zero arguments. The first of these weird formatters is actually found in the "%F" handler:

int FUN_001022aa(FILE *param_1,undefined8 param_2,undefined8 *param_3) {

return fprintf(param_1,"%52C%s",**param_3);

// ^^^^

}

Ah! So the "%C" consumes no arguments, leaving the "%s" to handle the one argument passed in, which will be printed as a string. When called from main, this argument is a global variable. In ghidra’s listing view, I saw that it couldn’t detect any other xrefs besides from main:

Next I looked at a few other formatters, starting with "%C". Every formatter has a similar declaration:

int printf_handler(

// FILE handle to write to

FILE* file,

// Format specifiers, like precision and max width to print

printf_info* info,

// arguments available to consume (varargs)

...);

And that printf_info struct is pretty important too:

/* from /usr/include/printf.h */

struct printf_info

{

int prec; /* Precision. */

int width; /* Width. */

wchar_t spec; /* Format letter. */

unsigned int is_long_double:1; /* L flag. */

unsigned int is_short:1; /* h flag. */

unsigned int is_long:1; /* l flag. */

unsigned int alt:1; /* # flag. */

unsigned int space:1; /* Space flag. */

unsigned int left:1; /* - flag. */

unsigned int showsign:1; /* + flag. */

unsigned int group:1; /* ' flag. */

unsigned int extra:1; /* For special use. */

unsigned int is_char:1; /* hh flag. */

unsigned int wide:1; /* Nonzero for wide character streams. */

unsigned int i18n:1; /* I flag. */

unsigned int is_binary128:1; /* Floating-point argument is ABI-compatible

with IEC 60559 binary128. */

unsigned int __pad:3; /* Unused so far. */

unsigned short int user; /* Bits for user-installed modifiers. */

wchar_t pad; /* Padding character. */

};

When a format string like "%-3.6lC" is handed to the "%C" handler, printf has already parsed out the modifiers into something like:

struct printf_info

{

int prec = 6,

int width = 3,

wchar_t spec = 'C',

unsigned int is_long:1 = 1, /* l flag. */

unsigned int left:1 = 1, /* - flag. */

/* other bits in bitfield set to 0 */

unsigned short int user = 0,

wchar_t pad = '\0',

};

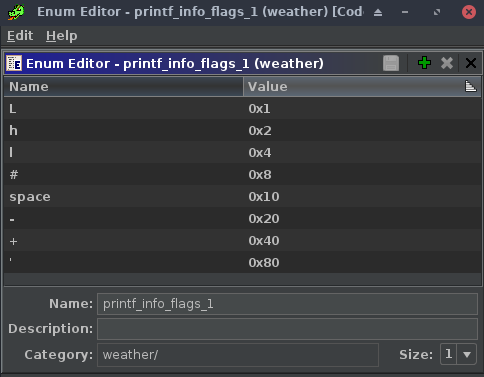

Ghidra is awful at displaying bitfields in the decompiler, but a workaround is to define an equally sized enum, with specific names for each bit position. Then it looks a little better.

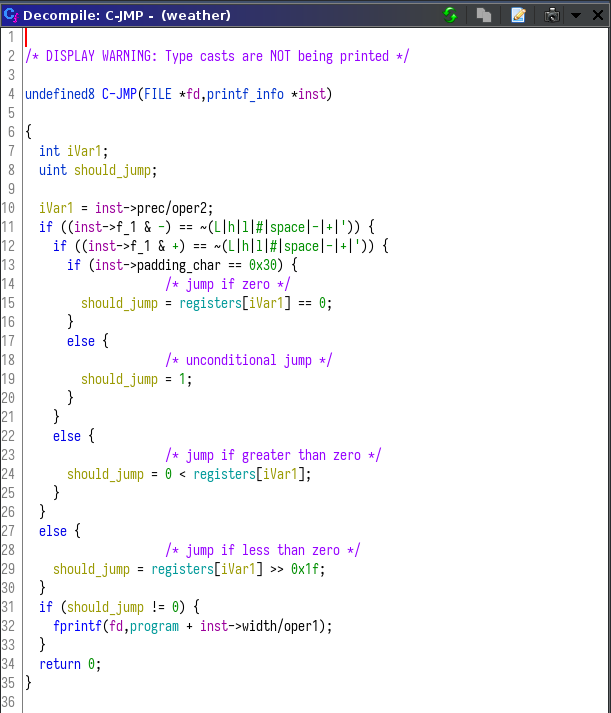

Eventually, after staring at the "%C" and "%E" handlers long enough, I knew each printf handler was some sort of virtual machine instruction that operated on global memory. "%C" modified control flow, by calling fprintf recursively at some offset from the base program.

The first instruction was "%52C" as called from the "%F" flag formatter.

Another important global buffer is the space where temporary values were read from and stored. My first guess for this buffer was a stack, but it made more sense as an array that holds register state.

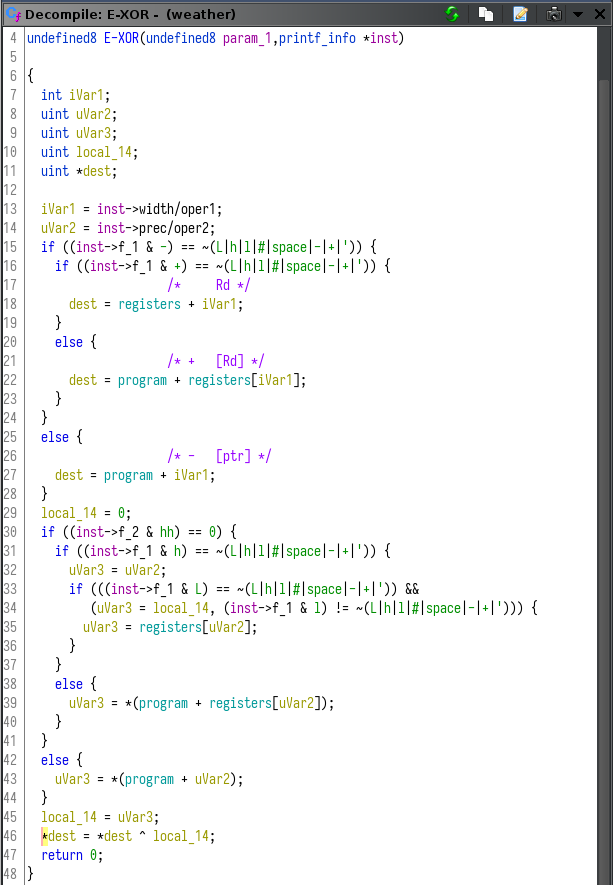

The arithmetic instructions all have a source, and a destination. Each operand can be a direct memory offset from the program base, a register, or using a register as a pointer to memory. They all parse how to operate on the source and destination operands, then apply some arithmetic.

First Disassembler

To figure out the virtual program that printf was executing, I wrote a disassembler. The task was to read the program string:

%52C%s\0%3.1hM%3.0lE%+1.3lM%1.4llS%3.1lM%3.2lO%-7.3C\0%0.4096hhM%0.255llI%1.0lM%1.8llL%0.1lU%1.0lM%1.16llL%0.1lU%1.200llM%2.1788llM%7C%-6144.1701736302llM%0.200hhM%0.255llI%0.37llO%0200.0C\0

…and figure out what it means in this virtual machine. The disassembler source is provided here with documentation. A commented version of an early disassembly attempt follows:

addr source inst

operation dest, source ("intel" syntax)

entry_point:

0: jmp --> 0x34 (jmp to start)

xor_loop:

r0: xor key (e.g. 0xabababab)

r1: buffer start

r2: buffer end

0x07: %3.1hM mov r3, [r1]

0x0d: %3.0lE xor r3, r0

0x13: %+1.3lM mov [r1], r3

0x1a: %1.4llS add r1, 0x4

0x21: %3.1lM mov r3, r1

0x27: %3.2lO sub r3, r2

0x2d: %-7.3C jn r3 --> 0x7 (jump to 7 if r3 is negative)

start:

0x34: %0.4096hhM mov r0, [0x1000] (user input!)

take first byte of user input: 0xab and make it 0xabababab

0x3e: %0.255llI and r0, 0xff

0x47: %1.0lM mov r1, r0

0x4d: %1.8llL shl r1, 0x8

0x54: %0.1lU or r0, r1

0x5a: %1.0lM mov r1, r0

0x60: %1.16llL shl r1, 0x10

0x68: %0.1lU or r0, r1 <- xor key

0x6e: %1.200llM mov r1, 0xc8 <- start xoring here

0x77: %2.1788llM mov r2, 0x6fc <- end xoring here

0x81: %7C jmp --> 0x7

0x84: %-6144.1701736302llM mov [0x1800], 0x656e6f6e (string "none")

0x98: %0.200hhM mov r0, [0xc8] <- read byte of next program

0xa1: %0.255llI and r0, 0xff

0xaa: %0.37llO sub r0, 0x25 <- check if it's a '%'!

xor key must be 0x54

0xb2: %0200.0C jz r0 --> 0xc8 (jump to 0xc8 if r0 is zero)

The instructions made just enough sense to figure out what it was: an xor decoder. Specifically, it reads the first byte of user input (0x1000 from program base is where the user initially enters a city name). Then it starts at 0xc8 from the program base, and applies that input as an xor key up to 0x6fc from the program base. Finally, it checks if the first byte xor’d ended up as a ‘%’. If so, it would jump there and keep executing more instructions!

I was very glad I took the time to write a disassembler.

I found out later that every conditional or unconditional jmp was really more like a conditional or unconditional call. The "%C" handler calls fprintf, which:

- pushes a new stack frame (or 2 or 3…) onto the main Linux program stack

- other custom handlers will execute instructions one after another

- consume no actual arguments to printf

- continue until

fprintfencounters a nul at the end of the format string:\0

In this sense, there is one implicit ret instruction that doesn’t have a custom format handler, but is just the natural returning from a fprintf call which happens at the nul terminator.

The stage 2 was very long, and I was getting tired of reading assembly. I wanted to add instrumentation and print out what was going on dynamically. I first tried to add break points using gdb, but I could only break on every add instruction when I really just wanted to break on a certain add instruction for example.

Second Disassembler

I decided to rework my disassembler to emit useful pseudocode that I could then compile as rust code. (hey, everything else is being rewritten in rust, right?)

Here’s a comparison of the old format to the new:

addr: --old-- --new--

0x07: mov r3, [r1] s.r3 = s.mem[s.r1 as u32 as usize];

0x0d: xor r3, r0 s.r3 ^= s.r0;

0x13: mov [r1], r3 [r1] = s.r3;

0x1a: add r1, 0x4 s.r1 += 0x4;

0x21: mov r3, r1 s.r3 = s.r1;

0x27: sub r3, r2 s.r3 -= s.r2;

0x2d: jn r3 --> 0x7 if s.r3 < 0 { label_0x07(&mut s); }

0x33: ret

^^^ a NUL terminator was here!

The machine only ever used registers 0-4 and RW global memory, so everything needed to represent virtual machine state is contained in this struct:

struct State {

// registers

r0: i32,

r1: i32,

r2: i32,

r3: i32,

r4: i32,

// memory

mem: Vec<u8>,

}

I had to manually fix up some of the disassembler transpiler output to create working rust code. For example, any target of a function call had to be an actual rust function. So I would separate that block under a new function, and end at the next ret found. Every function had the same type signature, a mutable reference to the State.

Memory accesses also had to be modified from the original syntax. Every VM read or write is 4 bytes wide, but has no alignment restrictions. In rust, unaligned memory access is undefined behavior. To get around this, and what turned out to be a killer feature of this emulator, was to make memory accesses a method on State.

impl State {

// read 4 bytes from memory

fn read(&mut self, src: i32) -> i32 {

// log the mem read

println!("reading <-- index {:x} {}", src, log_index(src));

// index as usize

let i = src as u32 as usize;

// copy memory bytes into temp buf

let mut buf = [0; 4];

buf.copy_from_slice(&self.mem[i..i + 4]);

// return value as little endian

i32::from_le_bytes(buf)

}

// write is similar

}

// example of a fully transpiled function:

fn stage2_28d(s: &mut State) {

s.r0 = 0x75bcd15;

s.r1 = s.read(0x1000);

s.r0 ^= s.r1;

s.r2 = 0x3278f102;

s.r2 ^= s.r0;

/* ... */

}

With the virtual program in this state, it was much faster to iterate, reverse engineer, and dynamically trace program state. You might have noticed the log_index function used in State::read(). This function was invoked on every memory access, read or write, and would tell me what buffer was being accessed. As I reversed out where user input was stored, or where the final flag string was being written, I would update this function.

fn log_index(index: i32) -> &'static str {

match index {

0x1000..=0x1100 => "[user input]", // user input "city name"

0x1190..=0x1290 => "[first pass]", // input lands here after XOR and add operations

0x1300..=0x1400 => "[RNG numbers]", // this range was actually prime numbers but whatever

0x1800..=0x1900 => "[flag output]", // points to `flag` global addr in binary, see ghidra

_ => "",

}

}

I could print out registers as well, which came in handy, but not as much as tracing memory and naming buffers.

Another killer feature of this approach was being able to quickly change the program. The last function call was to 0x28d and was conditional. It wouldn’t always run. I, being curious, wanted to know what would happen if the program did execute that function even if it wasn’t supposed to. So I added an else branch with a reminder that I was “cheating” by calling the function anyway:

if s.r0 == 0 {

// print flag?

stage2_28d(s);

println!("done with 28d");

} else {

println!("cheating");

stage2_28d(s);

println!("done cheating with 28d");

}

That last function was conditional on r0 being zero. The second to last function called set r0 by reading from an intermediate buffer, applying some static arithmetic, and or-ing those values into r0. If any part of that intermediate buffer was “wrong” then some bits in r0 will be set, and the final function would not get called. I called this function buffer_check.

Having the code in rust let me quickly copy and paste buffer_check and create another function buffer_create. I swapped out the OR instructions into memory write instructions. This effectively let me extract the desired, or “good boy” buffer into an easily read memory location.

Reversing

After all that work instrumenting and reversing how the VM executes instructions, it was a relatively quick matter to see what the program was doing and how to provide a winning input.

A full trace finally looked like this:

storing --> 33a1 to index 1388 [RNG numbers]

storing --> 33a3 to index 138a [RNG numbers]

storing --> 33ad to index 138c [RNG numbers]

storing --> 33b9 to index 138e [RNG numbers]

storing --> 33c1 to index 1390 [RNG numbers]

storing --> 33cb to index 1392 [RNG numbers]

storing --> 33d3 to index 1394 [RNG numbers]

storing --> 33eb to index 1396 [RNG numbers]

storing --> 33f1 to index 1398 [RNG numbers]

storing --> 33fd to index 139a [RNG numbers]

storing --> 3401 to index 139c [RNG numbers]

storing --> 340f to index 139e [RNG numbers]

storing --> 3413 to index 13a0 [RNG numbers]

storing --> 3419 to index 13a2 [RNG numbers]

storing --> 341b to index 13a4 [RNG numbers]

storing --> 3437 to index 13a6 [RNG numbers]

storing --> 3445 to index 13a8 [RNG numbers]

storing --> 3455 to index 13aa [RNG numbers]

storing --> 3457 to index 13ac [RNG numbers]

storing --> 3463 to index 13ae [RNG numbers]

storing --> 3469 to index 13b0 [RNG numbers]

storing --> 346d to index 13b2 [RNG numbers]

storing --> 3481 to index 13b4 [RNG numbers]

storing --> 348b to index 13b6 [RNG numbers]

storing --> 3491 to index 13b8 [RNG numbers]

storing --> 3497 to index 13ba [RNG numbers]

storing --> 349d to index 13bc [RNG numbers]

storing --> 34a5 to index 13be [RNG numbers]

storing --> 34af to index 13c0 [RNG numbers]

storing --> 34bb to index 13c2 [RNG numbers]

storing --> 34c9 to index 13c4 [RNG numbers]

storing --> 34d3 to index 13c6 [RNG numbers]

storing --> 34e1 to index 13c8 [RNG numbers]

storing --> 34f1 to index 13ca [RNG numbers]

storing --> 34ff to index 13cc [RNG numbers]

storing --> 3509 to index 13ce [RNG numbers]

storing --> 3517 to index 13d0 [RNG numbers]

storing --> 351d to index 13d2 [RNG numbers]

done generating buffer

reading <-- index 1000 [user input]

reading <-- index 1338 [RNG numbers]

storing --> 54 to index 1194 [first pass]

reading <-- index 1001 [user input]

reading <-- index 133a [RNG numbers]

storing --> 69 to index 1195 [first pass]

reading <-- index 1002 [user input]

reading <-- index 133c [RNG numbers]

storing --> 6c to index 1196 [first pass]

reading <-- index 1003 [user input]

reading <-- index 133e [RNG numbers]

storing --> 50 to index 1197 [first pass]

reading <-- index 1004 [user input]

reading <-- index 1340 [RNG numbers]

storing --> 6a to index 1198 [first pass]

reading <-- index 1005 [user input]

reading <-- index 1342 [RNG numbers]

storing --> 7f to index 1199 [first pass]

reading <-- index 1006 [user input]

reading <-- index 1344 [RNG numbers]

storing --> 56 to index 119a [first pass]

reading <-- index 1007 [user input]

reading <-- index 1346 [RNG numbers]

storing --> 6f to index 119b [first pass]

reading <-- index 1008 [user input]

reading <-- index 1348 [RNG numbers]

storing --> 74 to index 119c [first pass]

reading <-- index 1009 [user input]

reading <-- index 134a [RNG numbers]

storing --> 6d to index 119d [first pass]

reading <-- index 100a [user input]

reading <-- index 134c [RNG numbers]

storing --> 56 to index 119e [first pass]

reading <-- index 100b [user input]

reading <-- index 134e [RNG numbers]

storing --> 72 to index 119f [first pass]

reading <-- index 100c [user input]

reading <-- index 1350 [RNG numbers]

storing --> 75 to index 11a0 [first pass]

reading <-- index 100d [user input]

reading <-- index 1352 [RNG numbers]

storing --> 7d to index 11a1 [first pass]

reading <-- index 100e [user input]

reading <-- index 1354 [RNG numbers]

storing --> 84 to index 11a2 [first pass]

reading <-- index 100f [user input]

reading <-- index 1356 [RNG numbers]

storing --> 46 to index 11a3 [first pass]

reading <-- index 1010 [user input]

reading <-- index 1358 [RNG numbers]

storing --> 85 to index 11a4 [first pass]

reading <-- index 1011 [user input]

reading <-- index 135a [RNG numbers]

storing --> 68 to index 11a5 [first pass]

reading <-- index 1012 [user input]

reading <-- index 135c [RNG numbers]

storing --> 7c to index 11a6 [first pass]

reading <-- index 1013 [user input]

reading <-- index 135e [RNG numbers]

storing --> 6c to index 11a7 [first pass]

reading <-- index 1014 [user input]

reading <-- index 1360 [RNG numbers]

storing --> 4a to index 11a8 [first pass]

reading <-- index 1015 [user input]

reading <-- index 1362 [RNG numbers]

storing --> 83 to index 11a9 [first pass]

reading <-- index 1016 [user input]

reading <-- index 1364 [RNG numbers]

storing --> 75 to index 11aa [first pass]

reading <-- index 1017 [user input]

reading <-- index 1366 [RNG numbers]

storing --> 61 to index 11ab [first pass]

reading <-- index 1018 [user input]

reading <-- index 1368 [RNG numbers]

storing --> 86 to index 11ac [first pass]

reading <-- index 1019 [user input]

reading <-- index 136a [RNG numbers]

storing --> 79 to index 11ad [first pass]

reading <-- index 101a [user input]

reading <-- index 136c [RNG numbers]

storing --> d3 to index 11ae [first pass]

reading <-- index 101b [user input]

reading <-- index 136e [RNG numbers]

storing --> 85 to index 11af [first pass]

reading <-- index 101c [user input]

done reading input into first pass

reading <-- index 1194 [first pass]

reading <-- index 1198 [first pass]

reading <-- index 119c [first pass]

reading <-- index 11a0 [first pass]

reading <-- index 11a4 [first pass]

reading <-- index 11a8 [first pass]

reading <-- index 11ac [first pass]

done with buffer_check

cheating

reading <-- index 1000 [user input]

storing --> 7b465443 to index 1800 [flag output]

reading <-- index 1004 [user input]

storing --> 73727563 to index 1804 [flag output]

reading <-- index 1008 [user input]

storing --> 725f6433 to index 1808 [flag output]

reading <-- index 100c [user input]

storing --> 72756333 to index 180c [flag output]

reading <-- index 1010 [user input]

storing --> 65763173 to index 1810 [flag output]

reading <-- index 1014 [user input]

storing --> 3172705f to index 1814 [flag output]

reading <-- index 1018 [user input]

storing --> 7d66746e to index 1818 [flag output]

done cheating with 28d

First the program generated “RNG numbers” (really primes) that were always the same. Then, it read user input until a NUL terminator. It then xor-ed that input byte by an RNG byte. Then it took the index of that input, and added the number of steps to reach 1 following the Collatz Conjecture rules (btw Dirk just made a great video on that subject).

In pseudo code, the input-check algorithm is:

rng_numbers = [.....];

user_input = [.....];

first_pass;

for ii in 0..user_input.len() {

first_pass[ii] = (rng_numbers[ii] ^ user_input[ii]) + collatz(ii);

}

if first_pass ^ create_buffer() == 0 {

win();

}

Solving

I used the emulator to finally solve for the correct input value, and place that input string where user input is expected. Full emulation code here.

pub fn run() {

// default inits everything to 0 which is fine, I manually checked for any register reads that

// could have been uninitialized

let mut s = State::default();

// copy program bytes (program bytes exported from ghidra)

s.mem = include_bytes!("../mem").to_vec();

// extend out to include any reads/writes

s.mem.extend(&[0; 8000]);

// reverse the flag arithmetic and final check

{

// make the goodboy buffer

buffer_create(&mut s);

let goodboy = s.mem[0x1194..0x1194+0x1c].to_vec();

println!("goodboy {:x?}", goodboy);

// make the rng numbers buffer

generate_buffer(&mut s);

let numbers = s.mem[0x1388..0x1388+38*2].to_vec();

println!("numbers {:x?}", numbers);

// get some collatz numbers

let mut collatz_nums = Vec::new();

for c in 0..0x1c {

s.r0 = c + 1;

collatz(&mut s);

collatz_nums.push(s.r0 as u8);

}

println!("collatz {:x?}", collatz_nums);

// generate the winning input

let mut winning_bytes = Vec::new();

for ii in 0..0x1c {

let a = goodboy[ii].wrapping_sub(collatz_nums[ii]) ^ numbers[ii*2];

winning_bytes.push(a);

}

// put the right stuff into user input

s.mem[0x1000..0x1000+winning_bytes.len()].copy_from_slice(&winning_bytes);

let input = String::from_utf8(s.mem[0x1000..0x101c].to_vec()).unwrap();

println!("Winning input: {}", input);

}

// run the original virtual machine code

stage2_main(&mut s);

// extract the flag out of the machine memory

let s = String::from_utf8(s.mem[0x1800..0x1820].to_vec()).unwrap();

println!("Flag: {}", s);

}

Full solution repo is here. Thanks Google for a great ctf!

- Winning input:

TheNewFlagHillsByTheCtfWoods - Flag:

CTF{curs3d_r3curs1ve_pr1ntf}